Photo credits above: 1: Martin Mecnarowski; 2: John Polisar; 3: Washington State University, Wildlife Conservation Society, Panthera, Zamorano University, Honduran Forest Conservation Institute, Travis King, John Polisar, Manfredo Turcios; 4: Greg Homel

In 2013, a team of researchers using airborne LIDAR technology located the “Lost City of the Monkey God,” known to most Hondurans as the “Ciudad del Jaguar” (City of the Jaguar) or “La Ciudad Blanca” (The White City”), in the Rio Plátano Biosphere Reserve, within Honduran La Mosquitia. The LIDAR now provided clear visibility of a mysterious former city, previously heard of only in legends, now completely covered by rainforest. The city had been abandoned at the same time as the first wave of European conquest of the region, and had become enveloped in jungle ever since.

In some places, peeling back the layer of trees revealed symmetrical structures below. (UTL Productions, LLC) Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/05/are-these-the-first-ever-pictures-of-hondurass-lost-ciudad-blanca/275877/

A team of archaeologists and journalists led by Explorer Steve Elkins helicoptered into the site identified by the LIDAR in 2015 and confirmed the existence of a formerly substantially populated, advanced civilization – an expedition which led to multiple New Yorker articles, a book, and a movie. In 2017, an “ecological SWAT team” of biologists, primarily Honduran and Nicaraguan and supported by Conservation International, conducted a Rapid Biological Assessment of the site and surrounding region and documented hundreds of species, including some that were previously considered extinct and others completely unknown to modern science. The area was “full of jaguars,” thus leading the then Honduran President to rename “La Ciudad Blanca” to “La Ciudad del Jaguar.” Due to its remote location and rugged terrain, this stunningly unique and special place is a pristine ecological niche where very few human beings have spent time in the last 500 years.

But this critical conservation site and the area around it are at severe risk. La Mosquitia has become a hotbed for unregulated cattle ranching and other illicit activities including wildlife and drug trafficking. Deforestation for cattle farming has exploded – its proximity approaching the uniquely pristine valley where the Ciudad del Jaguar is located. Honduras has more bird species (763!) than any other country in north Central America, but the cattle farming is rapidly eliminating their natural habitat and putting these birds and many other animals in peril.

These forests are home to indigenous Miskitu and Tawahka communities who have been living in harmony with the biodiverse jungle around them for centuries. The Miskitu and Tawahka are ethnically distinct from the Maya, and have primarily lived from fishing in the Rio Patuca and small-scale cultivation of crops like yuca and rice. Small numbers of cacao trees, originally brought in to the region through trade with other indigenous communities, have grown wild in these forests, harvested sporadically by the Miskitu and Tawahka over the years, but cacao had not been a primary source of food or income for the communities – until recently.

In the photos above: Mariana Sánchez Salinas and son Justin in front of their home and farm in Wampusirpi; Argentina Cruz López holds a freshly harvested cacao pod; Jeff Anderson opens a cacao pod.

Cacao has historically (for millennia) been produced in the western region of Honduras, near Copán and the border of Guatemala. Over the last 15 years, government and private-sector programs have expanded cacao production to the north and east of Honduras, including in La Mosquitia. Significantly more cacao was planted by the communities in La Mosquitia as a result of these programs. One company, Cacao Fino y Maderables de Honduras (known to the bean-to-bar industry as Cacao Direct), set up cacao post-harvest operations in three regions: Omoa (north), Jutiapa (west), and Wampusirpi (a town of about 6,000 people in La Mosquitia). Notably, they built the area’s first centralized cacao post-harvest facility, in Wampusirpi, and started buying cacao in 2015. It became clear that the promotion of cacao agroforestry in La Mosquitia could provide an ecologically-friendly income generating model for local families and a clear alternative to cattle farming or involvement in illicit activities. This “cacao corridor” along the Patuca river, and near the Ciudad del Jaguar, is an area of immensely strategic conservation importance.

In the photos above: Florentino Portales in the Cacao Miskito fermentary; Florentino and Freddy Ramirez explain the drying process used at Cacao Miskito; Florentino loads a guillotine for a cut test of dried cacao.

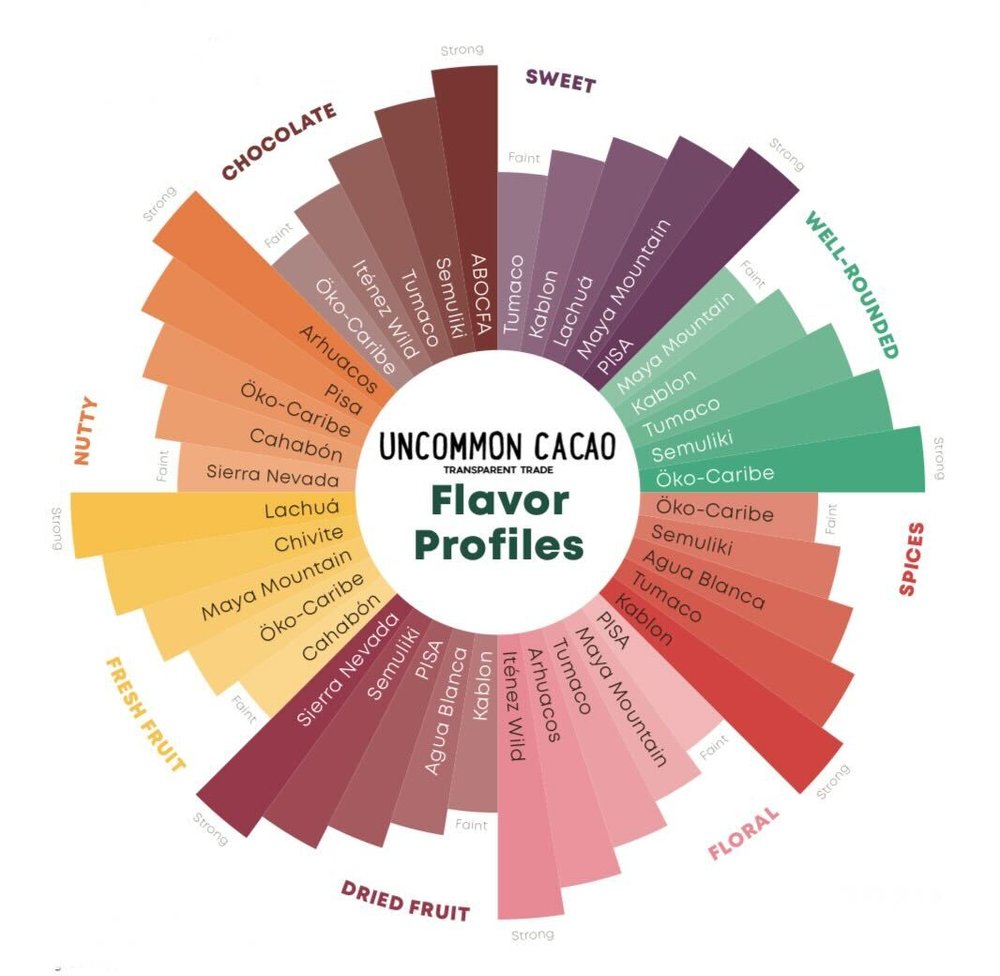

The post-harvest processing approach developed by the team at Cacao Direct, led in Wampusirpi by the visionary Florentino Portales (who deserves his own blogpost!), has caused many chocolate makers who taste this cacao to fall in love. It is deeply, richly chocolatey, without the fruit acidity common to many other Latin American cacao profiles.

The people who love this bean REALLY love this bean. Ron Sweetser, Cocoa Sourcing Manager at Dandelion Chocolate describes it as a “DC favorite.” Denise Castronovo, who has won at least 5 awards over three years for Castronovo’s “Lost City Honduras” chocolates is the one who put Uncommon in touch in July 2021 with John Polisar (formerly of the Wildlife Conservation Society and who has worked extensively on jaguar conservation in La Mosquitia) and Andrés Anchondo from the American Bird Conservancy, who was running an active project in Wampusirpi.

We learned through connecting with John and Andrés that unfortunately, due to COVID-related problems, Cacao Direct had ceased operations in March 2021. Exports had stopped, and financial, administrative, and commercial support to the producers in Wampusirpi had ceased. Not to be defeated by the challenge, the indefatigable Florentino worked with the existing network of producers to formally organize into an association and figure out what to do next. Cacao Direct retained ownership of the post-harvest facility, but gave Florentino and his team full access to use it for fermentation, drying, and storage of cacao. Denise, and other makers who had fallen for this unique bean, pleaded with us to help Florentino figure this out – and as we learned more about the incredible conservation importance of this region, we knew we had to get involved.

Over the summer of 2021, Uncommon dove into conversations with Florentino, Andrés, and local partner Issis Maradiaga Zavala, founder of SMART Consulting and EcosHN, who persistently supported Florentino in the development of Cacao Miskito and the pursuit of funding to enable the group to get back on their feet and exports to begin again. Uncommon ended up signing a preliminary contract for 5 MT and pre-financing 50%, sample unseen, in order to provide critical working capital to Cacao Miskito and to get the urgently needed buying and post-harvest process underway again.

In the photos above: Freddy Ramirez explains his cacao farming practices to Andrés from ABC and Emily; Florentino explains fermentation protocols to Emily; Emily translating the Uncommon Cacao Supplier Code of Conduct, Quality Expectations, and other partnership aspects to the team at Cacao Miskito; Emily and Florentino on Freddy’s farm.

Today, our 5 tons from that first contract landed in the warehouse in the US. We last saw this cacao when Emily, founder of Uncommon, traveled to Wampusirpi in February 2022 to meet Florentino and the producers, visit farms, collect samples and conduct quality evaluations. Most of the cacao from this first lot has been pre-sold, but we have a few bags available – if you are interested, please let us know. Even if we can’t offer you cacao from this first harvest, there will be more to come.

The potential of the bean-to-bar market to have a unique and long-term conservation impact in La Mosquitia, through transparent and stable market access and in partnerships with the American Bird Conservancy and local indigenous groups and NGOs, is huge. There are an enormous number of challenges – not least of which are the logistics. There are no roads connecting communities in the cacao corridor to each other or to any other roads, so this cacao was purchased fresh by boat (long, slender boats called “pipantes”) and brought to the facility by boat. All of the dried cacao was taken out by pipante on a 9+ hour river journey, carried in pick-up trucks another 9 hours to Catacamas, the nearest city, then trucked across Honduras to the eastern Atlantic port. But we know that this cacao is worth it.

There is so much more to share – and that we will share in the future – about this exciting and ambitious specialty cacao operation in Wampusirpi. We could not be more honored and excited to have the opportunity to collaborate with Cacao Miskito, with Florentino, with Issis, and with Andrés, Marci, and the American Bird Conservancy.

Check back in our social media for updates on the makers who are using these beans and where to buy their chocolate!

Florentino Portales, manager of Cacao Miskito, gives a “thumbs up”